introduction

Oedipus: The Riddle of Desire

In 1896 Freud wrote to Wilhelm Fliess, ‘I have found, in my own case too, [the phenomenon of] being in love with my mother and jealous of my father, and I now consider it a universal event in early childhood’. This insight led him to embark on an analysis of Sophocles’ play Oedipus Rex, which would begin a careerlong engagement with the Oedipus myth.

In emphasising the universal significance of Oedipus Rex, Freud was drawing on a philosophical tradition inherited from Schelling and Hegel, who thought the play symbolised the human search for freedom and the discovery of self-consciousness. For Freud, Sophocles’ play did not have universal significance because of its symbolic meaning, but because of the material that it dealt with: parricide and incest. In killing his father and marrying his mother, Oedipus enacts our infantile desires, which have undergone repression. The play retains its influence for a modern audience because it allows us to enjoy the fulfilment of our unconscious desires at a safe distance.

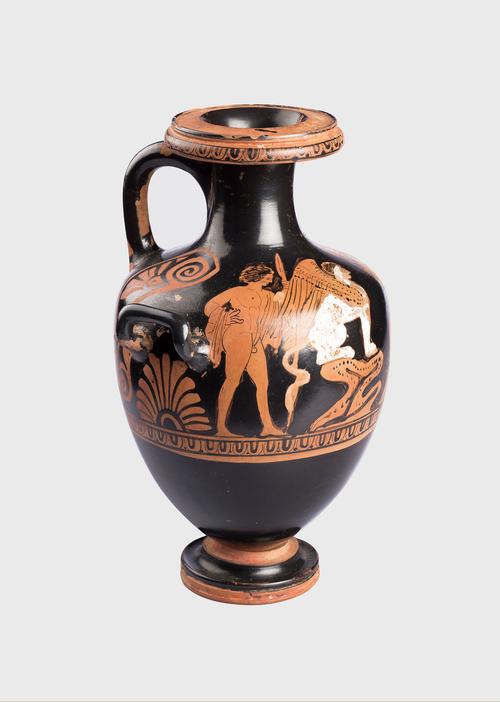

Charcot had described hysterics as ‘sphinxes who defy deepest anatomy’, and it is Oedipus’ encounter with the Sphinx, in which he solves the famous riddle, that was most represented in Freud’s collection. As the patient entered Freud’s consulting room, they would be met with a print of Ingres’ Oedipus and the Sphinx, depicting Oedipus in the very act of riddle-solving, suggestive perhaps of the psychoanalyst unravelling the riddle of the hysteric’s symptom.

Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex exists as both a material text, a unique object to be mined and decoded, as well as an exemplary representation of the human condition, defined by what Freud would later call the ‘Oedipus Complex’.

Red-figure hydria

Greek, Classical Period

380 - 360 BCE