introduction

Moses: The Return of the Repressed

In his final, genre-defying work, Moses and Monotheism (1939), Freud returned to a figure who had fascinated him throughout his life. In 1914 he had written an important study of Michelangelo’s sculpture of Moses, but Moses and Monotheism represented Freud’s lifelong ambivalence towards his Jewish heritage. The iconoclastic nature of Freud’s thesis is apparent from the very first sentence which announces his intention to ‘deprive a people of the man whom they take pride in as the greatest of their sons’.

Echoing the Oedipal narrative of Totem and Taboo, Freud argued that Moses was in fact an Egyptian prince and follower of the heretical monotheistic pharaoh Akhenaten. Moses imposed the harsh strictures of his monotheism on the Jewish people, who subsequently murdered him in an act of rebellion. The later development of Jewish monotheism, with its ‘ever stricter, more meticulous and more trivial’ commandments was for Freud an example of the ‘return of the repressed’, caused by an unconscious sense of guilt for the original murder of Moses. However, this traumatic history also propelled the Jewish people into making great advances in intellectuality, or Geistigkeit, and turned the story of the Jews into a universal history of mankind

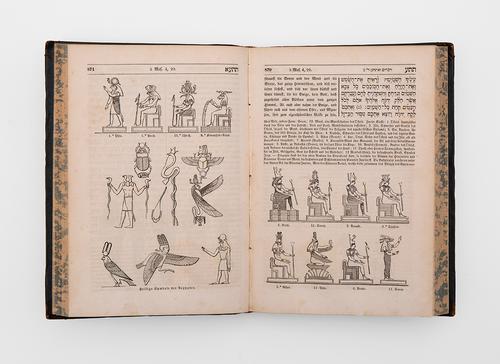

Freud admitted that bible stories had a profound effect on him from an early age. In Moses and Monotheism, he describes the Bible in the same manner as Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex, as a work that contains different layers of meaning. Freud suggests that the biblical text is a document that both ‘covers over’ the original murder and at the same time reveals it, in the form of textual traces. The tools developed by psychoanalysis allowed the reader to unearth the meaning behind these textual traces.